Brick Streets of Freedman's Town

|

Brick streets are becoming extremely rare in Houston, and in my neighborhood there are only two: Andrews and Wilson. The two intersecting lanes just west of downtown cut a slice out of Freedman's Town, so named for its population of freed slaves founded just after the Civil War to accommodate an influx of freed slaves migrating to Houston to seek jobs. There isn't much left of the African American community that once made its home here, and nearly all of the real estate been demolished to make way for upscale apartments and condominiums housing a largely white population. The new residents have plenty of income to live within the shadow of the high-rise businesses of downtown, and most have no school-age children to dictate the imperative access to a good education .

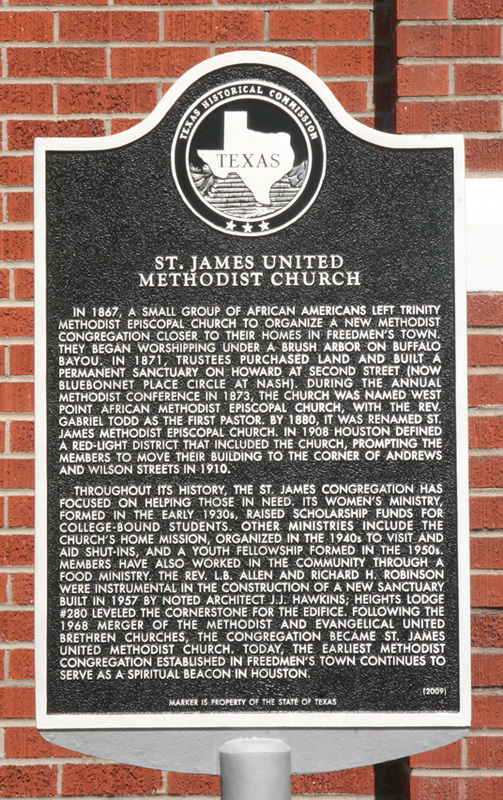

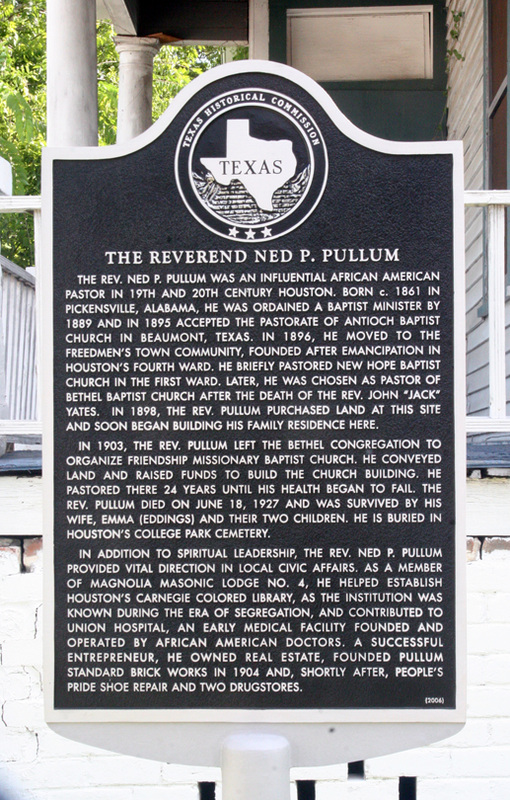

Andrews Street even today bears the vestige of railroad tracks from the only line circling through Freedman's Town to bring black laborers from their homes to work in other parts of the city. Just where the trolley line curves north onto Wilson Street a couple of houses bear historical markers noting the homesites of two prominent African American citizens. Rutherford B. Yates, a son of John Henry (Jack) Yates, lived at 1318 Andrews in a modest cottage partly restored. Rutherford was a printer, and the son of John Henry (Jack) Yates, minister and namesake of Yates High School near the University of Houston. Just across the street at 1319 a similar house was the home of Ned Pullam, a preacher and entrepreneur whose business ventures included a brick factory which may have produced the bricks for the streets. Citizens of the neighborhood petitioned to have the trolley route paved but the government balked, so the citizens banded together and paved the streets themselves. Andrews Street is so narrow the trolley must have made for quite a spectacle lumbering down the lane, stopping here and there to pick up workers and carry them to their jobs in other parts of the city. As the trolley car made the sharp bend at the corner of Andrews and Wilson streets, I can imagine the bell clanging loudly to warn of its approach. The trolley would have filled the narrow street to capacity, leaving little room for pedestrians, much less delivery vehicles such as ice trucks or milk wagons. In the turn of the century world of Houston, many deliveries would have been borne by draft animals, and automobiles would have been very few indeed. John Henry "Jack" Yates (1828–1897) was one of the first freed slaves to live in Freedman's Town when it was founded just after the Civil War, working as a drayman by day and preacher by night. When Antioch Baptist Church was founded in 1866, Yates was named as its first pastor. Yates bought several lots on Andrews Street in 1869, and at #1318 he built the house in which he raised a large family which included his eldest, Martha, and sons Rutherford B., and Willis. Rutherford built a house next door at #1314 in 1912 to continue his family's connection in Freedman's Town. Having been taught to read as a young slave child, (against the prevailing laws) by his mistress, Jack cared a great deal about education. Five of his children taught school, and his daughter Maria did mission work around the country. He was a founder of Houston Academy for black children, and Bishop College in Marshall after trying to locate the school in Houston. When his first wife Harriet died, he married Annie Freeman and had one more son, Paul. In 1891 he organized Bethel Baptist Church and was pastor there until his death. In 1926 Jack Yates High School was named in his honor. Jack's son Willis owned and operated a steam cotton gin in the 1880's, perhaps the only black man in the county to do so. Rutherford was raised by white missionaries (?) and received his degree from Bishop College. He was a teacher and founder of Yates Printing Company. Rutherford and Paul wrote The Life and Efforts of Jack Yates, later published by Texas Southern University Press in 1985. Paul graduated from Prairie View A&M and taught at Houston Academy. In 1994 John Henry Yates's home at #1318 was moved from Andrews Street to Sam Houston Park where tours are available to see how freed slaves lived in the late 19th century. |

|

by Boneta Harris: " The ordained entrepreneur: Rev. Nathan ("Ned") P. Pullum

Rev. Pullum was born in 1862 in Pickensville, Alabama. After serving as pastor at Antioch Baptist Church in Beaumont, Texas, he moved to Freedmen's Town. He also pastored New Hope Baptist Church in First Ward for a brief period of time and subsequently became pastor of Bethel Baptist Church in Fourth Ward when its founder and first minister, Rev. John Henry "Jack" Yates (http://www.examiner.com/x-58697-Fourth-Ward-Christianity-Examiner), died in 1898. Rev. Pullum bought land and raised $25,000 to construct Friendship Missionary Baptist Church, which he organized in 1903 and pastored for 24 years. Rev. Pullum was not only an excellent minister, he was also a very busy businessman who was active in the community. He was a member of Magnolia Masonic Lodge No. 3. He helped to establish Houston's Colored Carnegie Library. He was a successful real estate person who sold land to black doctors who founded and organized People's Sanitarium in 1917, a hospital for African Americans, which was solely owned and operated by black doctors. In 1904, Rev. Pullum also founded Pullum Standard Brick Works. (Since his six-room Colonial-style house was one of the first in Freedmen's Town to be made with bricks, it is easy to recognize that his company assisted in the construction of his family's home.) He also operated People's Pride Shoe Repair from his home. Although Rev. Pullum was very active in the community during his lifetime, he continued to minister to his congregation until death on June 18, 1927. Rev. Ned P. Pullum is buried in College Park Cemetery in Fourth Ward." |

References:

Reverend Jeremiah Smith

By Debra Sloan, RBHY historical researcher/advisory board member An early and important citizen of Freedmen's Town was the Reverend Jeremiah Smith, a black minister who lived and worked in the district. He is listed in the City Directory of 1890-91 as a resident and owner of a restaurant on Andrews Street. According to news reports and oral tradition relates the Reverend Jeremiah was an evangelist who used to preach under a tent that he erected on an empty lot at the corner of Gillette and Genesee streets. It is also said that his congregation laid the original bricks along Andrews Street, when the city refused to pave it in the early part of the century. He played an instrumental role in 1910 in the founding of Union Hospital, which once stood on the N.E. corner of Andrews and Genesee- the first hospital in Houston and, perhaps in the state (Post 1984:6), that was owned and operated by blacks. Brick Street Research Continues By Carol McDavid, Ph. D. and David Brunner, Ph.D. Co-Directors, YCAP RBHY recognizes that the historic brick streets are a ‘defining element of the historic character’ of National Historic District Freedmen’s Town. City of Houston’s Public Works Dept. and private contractors are destroying the streets daily. The City of Houston’s current inappropriate plan places the streets in imminent danger. RBHY strongly supports the community’s need to have street and street/sewer repairs done, but believes that this is possible without tearing up the historically important streets. [A copy of the RBHY review of the Carter & Burgess plan and our recommendations for proper restoration is available.] The streets are significant not only because the ancestors built them, but also because the patterns of the laid bricks, especially in the intersections, are very unusual. Initial research by RBHY archaeologists (who have consulted several nationally known scholars, including noted folklorist Gladys Marie Fry and archaeology professors Kenneth L. Brown and Christopher Fennell) have provided strong support for the idea that these Freedmen’s Town “crossroads” are worthy of serious documentation and study. Studies in folklore, religion, art history, archaeology, and anthropology have revealed similar patterns in other African and African American material culture contexts. As one scholar put it to us recently, “We’ve studied African connections to African American art, music, and many other things – but we haven’t studied streets. This could be very important.” The research continues, in the hope that it will provide the information to the streets before it is too late. Your help is needed to convince the new city administration that saving this historical treasure is vitally important. |