Interurban Viaduct

|

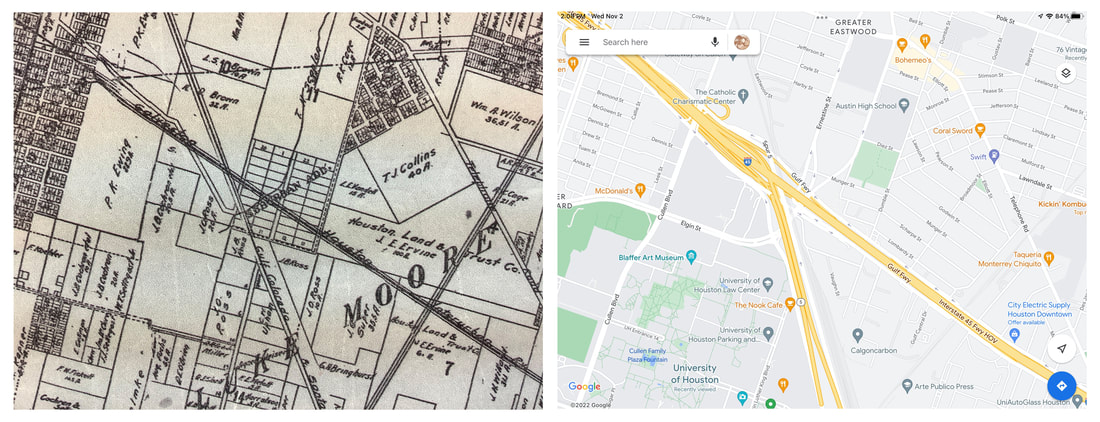

10 November 1915: The fare for the Interurban Electric train was $1.25 and trains left hourly for a trip taking an hour and forty minutes. The Like the streetcars, it was electric, unlike the steam railroad below carrying freight and some passengers. Hurricane August 1915 disrupted service for a few weeks due to damage at causeway approaches.

The Houston Depot of the Galveston-Houston Interurban was at 1006-1008 Texas just east of Main Street [See Interurban Depot and Texas at Fannin.] |

12 October 2022: As a benefactor and strong supporter of mass transit, I used the Houston Metro App to navigate the 3.5 miles from my wifi spot at The Corner Bakery at Main and McKinney to the Eastwood transit Center east of the University of Houston. At the transit center it was an easy walk to cross the Gulf Freeway feeder and around the curve of Ernestine to the location where the three rail lines of the Union Pacific Railroad remain from 1915. Where the Interurban viaduct once crossed the steam rail lines, the 23 lanes, access ramps, and feeder roads of the massive Gulf Freeway loom overhead. After many photographs from various angles and one purloined souvenir railroad spike, I continued my walk over to the University of Houston on the other side of the Gulf Freeway where a bus stop awaited me, and soon I was brought back to downtown.

|

|

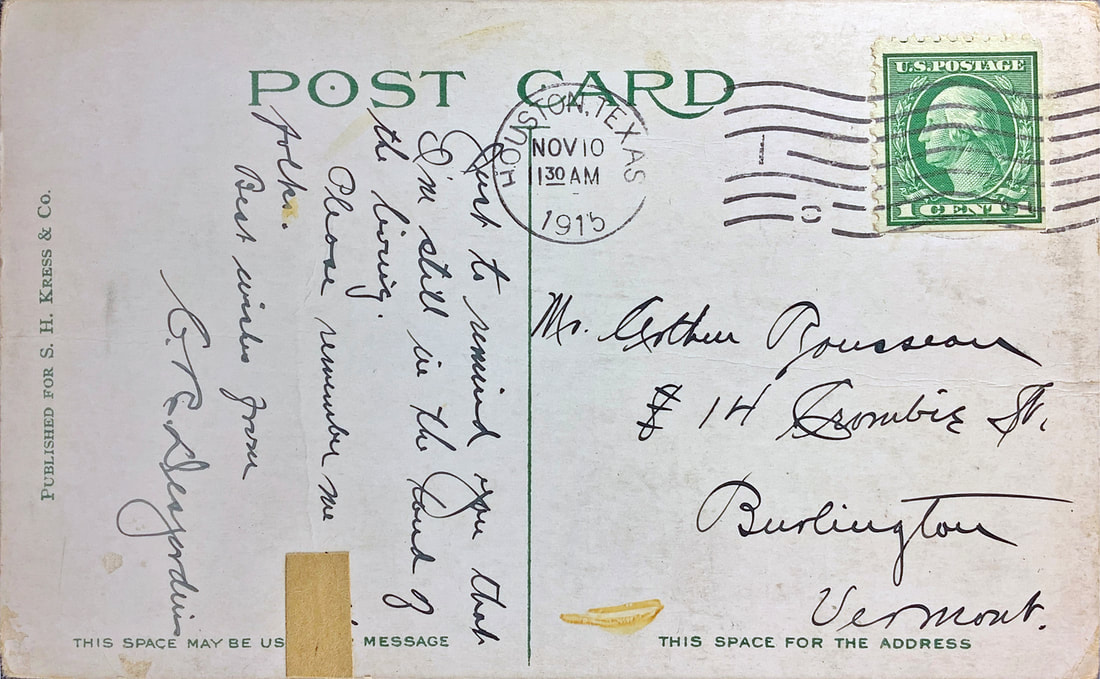

Postmarked: 10 November 1915; Houston, Texas

Stamp: 1c Green George Washington #405 To: Mr. Arthur Rousseau 14 Crombie St. Burlington, Vermont Message: Just to remind you that I’m still in the land of the living. Please remember me [tape] folks. Best Wishes from C. R. Desjardins When he posted the card, it had been a couple of years since Charles Desjardins had seen his cousin Ida’s husband Arthur Rousseau, and something about Southeast Texas may have reminded him how they had grown up neighbors in Burlington, VT. Charles was eight years younger than Arthur, and after his father Jules died in 1898, the family struggled to maintain their home at 139 Interval Avenue just a couple of blocks from the Rousseau’s on Crombie Street.

Charles was one of six children of Jules and Odile Desjardins: Joseph (1873), Paul Alphonse (1879), Alvina (1883), Charles (1887), Frederick (1890), and Antoinette (1896). The eldest, Joseph seemed unable to take much responsibility, making a poor living sharpening tools and occasional roofing jobs; when he died in 1939, Charles was the informant reporting that Joseph had not worked regularly for 15 years. Paul became a military man and was garrisoned in Ft. Russell, Laramie, Wyoming, later settling in Fort Collins for the rest of his life. When their father Jules died in 1898, much of the responsibility for the family fell to Charles. By 1915 when he traveled to Houston, he was the bulwark of the family economy. Together the other family members cooperated and pooled their resources to help out: Alvina (14 years older than Charles) worked in a garment factory and took in seamstress jobs, Joseph (10 years older) contributed what he could from his odd jobs, Frederick (2 years younger) cleaned railroad cars, and Antoinette (8 years his junior) took a job in a button factory. Charles worked as a traveling salesman selling wholesale hardware, this livelihood probably brought him to Houston, so very far from Vermont. Burlington in 1915 was a thriving historic town of about 20,000 on the banks of Lake Champlain, but Houston was entering a period of explosive growth, doubling every ten years to a population of more than 100,000 when Charles visited. He had moved from Burlington to Rochester, New York 3 years earlier, bring his mother and the rest of the family with him, except his brother Joseph, who stayed behind in Burlington. Charles’ cousin, Ida Roberge Rousseau, was the daughter of his Aunt Elizabeth Desjardins Roberge. The Desjardin’s, Rousseau’s, and Roberge’s were all French Canadian in origin, coming to Vermont from Quebec in the last half of the 19th century. The older generation were French speaking, and the younger members may have been somewhat conversant. An interesting aspect of the Quebecois naming convention was the use of “dit” to designate alternate surnames. Charles signs his postcard C. R. Desjardins where the R stands for “dit Roy” for his alternate surname. The alternate surname largely transformed into a middle name in Charles’ generation, and the “dit” designation has now become an anachronism. |

The message Charles sent to Burlington was a nostalgic plea to remember him to the family he left behind, his Aunt Elizabeth Roberge and the Rousseau’s. He was perhaps yearning for a simpler time in his life when he had fewer responsibilities. He was still a bachelor when he wrote the postcard, and would not marry for another five years. Arthur and Ida Rousseau had been married since 1905 and had a son Joseph Robert Rousseau who was about 6 when the postcard went out. What provoked Charles to chose a railroad-themed image isn’t spelled out, but it may well be that railroads were central to his life as a traveling salesman. The Interurban was a rather unusual form of railroad travel [See LINK Interurban], providing mostly day-trippers a quick way to get to Galveston Island. Familiar with lakes such as Lake Ontario and Lake Champlain, Charles may have taken the Interurban to Galveston for a chance to see the open ocean at the Gulf of Mexico.

In 1920 Charles chose for his bride Edna Marcelina Jacques, daughter of Clement Jacques, a farmer in Morrisonville, a small community near Schuyler Falls in Clinton County, NY. They married there, Edna working as a teacher, her sister Mae as a stenographer. The small city of Plattsburgh (population 10,000 in 1920) was a ferry ride away from his family in Burlington, so perhaps they met as he traveled between Rochester and Burlington. By 1925 Charles had brought the family to Schuyler Falls to live next to his father-in-law where Edna remained a teacher and became mother to their son Paul born in 1921. They moved to Plattsburgh by 1930 where the family remained. Paul attended Yale University where he studied philosophy; when WWII arose, he learned Japanese well enough to be assigned as naval officer commanding Marines in the first wave at Iwo Jima. He became a professor of Philosophy at Haverford College outside of Philadelphia, PA noted for his innovative and engaging methods of teaching. Charles died in Haverford, PA in 1981 and was buried in St. Peter’s Cemetery in Plattsburgh, joining his wife, Edna who had died in 1977. Also in St. Peter’s are her parents, Clement Jacques (1855-1930) and Margaret P. Soula Jacques (1861-1949), sister Mae Jacques Cox (1897-1987) and brother-in-law, Fabian Christopher Cox (1897-1978). His siblings and mother who remained in Rochester are buried in Holy Sepulchre Cemetery there: Odile DesJardin (1857-1922), Alfred (Frederick) Desjardins (1890-1961), Alvina Desjardins (1883-1972), Antoinette Desjardins (1896-1986). Charles’ correspondent and cousin Arthur Rousseau lived only 7 years after receiving the postcard, and was buried in Old Mount Cavalry Cemetery in Burlington. After a widowhood of more than 38 years his wife Ida C. Roberge Rosseau (1880-1961) was buried beside him. Their only son, Robert Joseph Rosseau (1909-1994) is buried in Old Mount Cavalry Cemetery as well, joining many Roberge relations: Joseph Roberge (1849-1909) and his wife Elizabeth Desjardins (1851-1945), the sister of Jules Desjardins, the father of Charles and his siblings. Also in this cemetery are Emelie Desjardins Rioux (1841-1906) and her husband Antoine Rioux (1828-1901), most likely related as well. |

|

1910 Map of the City of Houston and Vicinity, Texas Map & Blue Print Co. 317 1/2 Main St. Houston, Texas [Collection of the Houston Public Library, Texas Room].

|